Winter Solstice and Pagan Holidays that Underlie Christmas

What is the meaning of the winter solstice and why was it celebrated? Is there a connection between the pagan winter solstice traditions and Christmas? Why do we celebrate Christmas on December 25th? Does the Bible give the date of Christ’s birth? In this post I answer these and other similar questions.

What is the winter solstice?

The winter solstice is the day with the shortest period of daylight and the longest night of the year. In the Northern Hemisphere it occurs on the 21st or 22nd of December. The solstice, as an astronomical event, is calculated rather than observed. It is impossible to see it because the movement of the sun is very slow. Moreover, around the time of the solstice the sun’s daily path across the sky appears to be the same for several days.

The word ‘solstice’ therefore means the ‘standing of the sun’ in Latin. It describes a pause in the seasonal movement of the sun’s daily ark. The ark is ‘standing still’ before it becomes visibly higher after the winter solstice, or visibly lower after the summer solstice.

Why is the winter solstice celebrated?

For ancient people the winter solstice was an important period that marked the beginning of a new year and a new agricultural season. They thought of it as the time when the sun is reborn.

After the summer solstice in June the days become shorter, and by October the hours of daylight are shorter than the hours of the night. In November and December the nights are particularly long. The trees have shed their leaves, and the insects and many birds have disappeared. The land looks barren. It is the time of deep sleep in nature.

For humans it was the time of celebration and also prayer. Hopefully, all the hard work of preparing for severe winter weather, storing food, gathering fuel and providing a warm home has been completed. There was therefore an opportunity to rest and enjoy the results of one’s labour. At the same time, ancient people understood better than us how much our lives depend of the sun’s return. There was probably fear that it may not come back, and joy when its return became obvious.

Did Christmas begin as a pagan holiday?

The Bible does not give the date of Christ’s birth. Early Christian writers therefore made different guesses, most commonly placing it in spring. The earliest document that gives the date 25 December is the calendar of Philocalus, produced in 354, apparently in Rome. By the end of the 4th century this date became widely accepted as the day of Christ’s birth. Its conventional nature, however, and connection with earlier pagan religion was evident to contemporaries.

Ronald Hutton in his account of the origin of Christmas cites ‘admirably candid’ testimony of a Christian writer, the Scriptor Syrus, in the late fourth century:

‘It was a custom of the pagans to celebrate on the same 25 December the birthday of the Sun, at which they kindled lights in token of festivity. In these solemnities and revelries the Christians also took part. Accordingly when the doctors of the Church perceived that the Christians had a leaning to this festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true Nativity should be solemnized on that day’.

Fifth-century Christian authors, such as Augustine of Hippo, felt it was necessary to remind the people that it was the birth of Christ, and not of the sun that they celebrated on that day. The placement of Christ’s nativity around the time of the winter solstice created opportunities for confusion. At the same time, however, it was profoundly symbolic. If Christ was indeed ‘the light of the world’, such date was highly appropriate.

Pagan traditions that underlie Christmas: ancient Rome

The Romans had their own feasts around the time of the winter solstice. They celebrated the feast of Saturn (Saturlania) on the 17th of December, and festivities continued for several days afterwards. Some traditions of this popular feast were similar to the traditions of Christmas. Shops, schools, and law courts stayed closed, and people exchanged presents – especially candles, the symbols of light.

During the Saturnalia the spirit of the carnival and the logic of topsy-turvy ruled. Masters and mistresses waited at mealtimes upon their servants. Men threw lots to choose one of their number as king and followed the ‘king’’s absurd orders. According to the Roman writer Lucian, this could include shouting out something disgraceful about oneself, or picking up a girl and carrying her three times around the room.

More feasting occurred on the 1st of January, known as the ‘kalends’ of January. It marked the start of the new year in imperial Rome. People exchanged gifts to bring luck in the new year, particularly dried figs, dates and honey. As the Roman poet Ovid explains in his poem Fasti (1.188), it was to ensure that ‘the whole course of the year may be sweet, like its beginning’.

Ovid also mentions that another common new year gift was money. He wisely comments:

‘How little you know about the age you live in if you fancy that honey is sweeter than cash in hand!’ (Fasti, 1.189).

Winter solstice in pagan religion of the Stone Age

There is plenty of evidence that the winter solstice was important in ancient celebrations and rituals. Some prehistoric monuments built in Britain and Ireland around 3200–3000 BCE have important solar alignments. They are oriented to sunset or sunrise at midwinter, midsummer or the equinoxes. Thus, an enormous passage grave of Newgrange in the Boyne valley of Ireland has a special opening above its entrance. Through it the rising sun at midwinter could shine even when the entrance was blocked up.

Another huge passage grave of Maes Howe on Orkney Islands shares many features of its design with Newgrange. They are roughly of the same date. One of the common features is a gap above the blocking stone at the grave’s entrance. Through it the midwinter sun shines into the inner chamber. The difference with Newgrange is that the moment is that of sunset and not of sunrise.

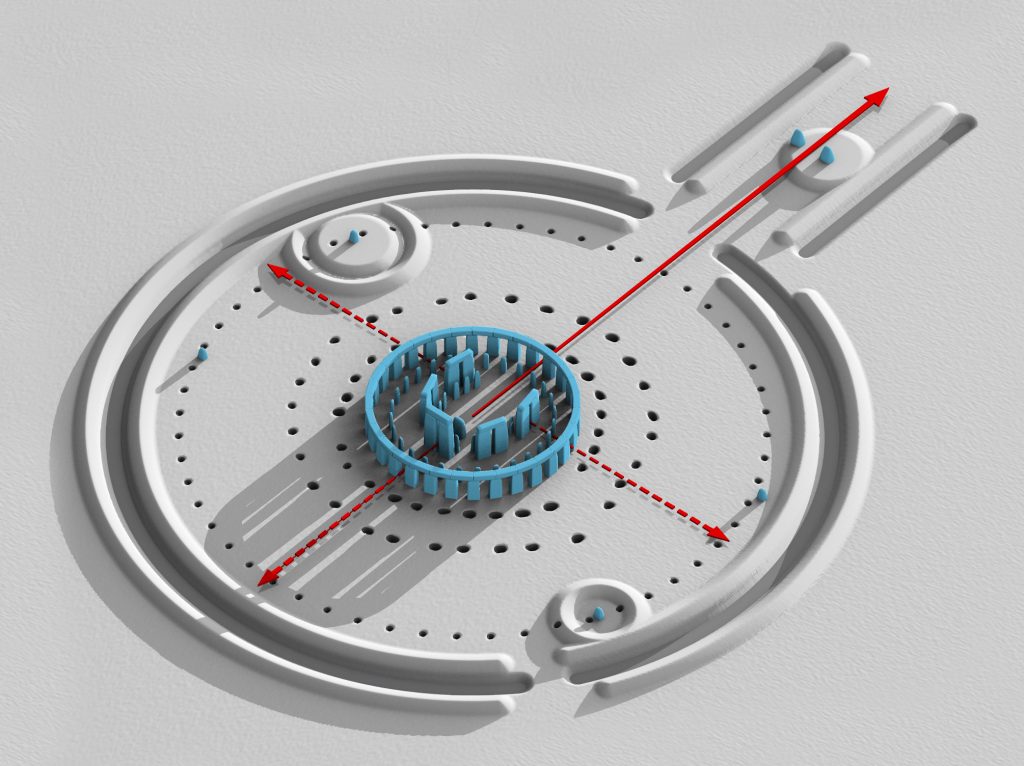

Solar alignment is also present in some stone circles of the third and early second millennium BCE, most famously at Stonehenge. Around 2100 BCE it was reconstructed to provide an alignment upon the midsummer sunrise through its only entrance. It was also given a corresponding orientation upon the midwinter sunset, through the uprights of the ‘great trilithon’ behind its centre.

Pagan winter solstice celebrations in England and Scandinavia

Several pagan feasts celebrated at winter solstice in Northern Europe form the roots of modern Christmas. An interesting example of this is a testimony of an Anglo-Saxon historian Bede, writing around the year 730. He states that the most important annual festival of the English before they became Christians was what they called the Modranicht, or ‘Mothers’ Night’. They celebrated it on the 24th of December.

According to Bede, this night started the new year of the Anglo-Saxons, and they marked it with religious rites. Admittedly, Bede had only a limited knowledge of these earlier traditions, as he acknowledged himself. The term Modranicht does not occur in any other early English or Continental sources.

Yet another predecessor of Christmas was Yule, a festive winter period of the ancient Scandinavians and Anglo-Saxons. The derivation of its name is unclear, but it may be related to words meaning a ‘wheel’. This would make sense, because a wheel is a common symbol of the year and the change of seasons. A wheel turns at the solstice when the sun’s orb pauses and then starts growing higher or lower.

Medieval Scandinavian literature also mentions a pagan feast in October that was called the ‘Winter Nights’. It opened the festive season, whereas Yule was the height of the festive season – the midwinter and the beginning of a new year. There were important sacrifices at both feasts.

Winter solstice traditions

The winter solstice celebrations often involve light. This includes bonfires, candles, the Yule log, fireworks and modern Christmas lights. The light symbolizes the rebirth of the Sun, the increase in the length of day and the eventual return of warmth.

Another common theme is the continuing presence of life in the depth of winter. Many winter solstice traditions remind us that nature is not dead, but is only resting. Evergreen plants that apparently often featured in ancient winter solstice celebrations symbolize the hope that life is about to return. Such plants included pine and fir, holly and ivy, yew, box, bay, myrtle and other evergreens. The same symbolism is evident in the use of flowering plants, such as forced cherry branches (St Barbara flowers) and cherries grown in containers in winter. Cherries planted in pots and made to flower at Christmas provided alternative Christmas trees in medieval and early modern Germany.

Other flowers traditionally given as gifts and used to decorate homes at Christmas have the same significance. They include hyacinths, paperwhite narcissus, hellebores (a Christmas rose) and poinsetties. They symbolize the flowering of fields in spring that is no longer that far away. A Christmas tree, in addition to its Christian symbolism, has a similar meaning. Decorated with an abundance of fruit, nuts, animals, flowers and ‘everything and more’, as a girl says in a story by Charles Dickens, it symbolizes prosperity we hope for in the coming year.

Was Christmas stolen from pagans?

It would be an exaggeration to say that Christmas was stolen from pagans. Celebrating Christ’s birth is, of course, a Cristian tradition. However, the date chosen for Christmas was close to the winter solstice, a highly important festive season in ancient religions. Christmas therefore took on the symbolism and some of the traditions of the winter solstice.

When Christianity became established, the celebration of Christ’s nativity replaced the earlier feasts of the winter solstice. It did not eliminate, however, the closely related New Year celebrations. Throughout the medieval period Christian writers in Britain warned against celebrating the pagan New Year’s Day and attempting magic and divination on the occasion. Many rites and customs of New Year’s Eve and Day aim to predict the future and ensure good luck. They continued into the early modern period and many still survive today.

We have lost the sense of our total dependence on the sun and of the importance of the period of rest in nature. Yet sleep is essential in spite of nature’s seemingly endless vitality. Seeds and bulbs cannot grow without a period of dormancy. The winter solstice is the time to align ourselves with the cycle of seasons, so that we could enjoy both the period of rest and the re-birth of light.

To learn more about Christmas, New Year and the winter solstice read the following:

Ronald Hutton, ‘The Origins of Christmas’, in The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. An excellent account of ancient and modern, religious and secular celebrations in Britain.

The Oxford Companion to the Year: An Exploration of Calendar Customs and Time-Reckoning, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. An authoritative reference book for ancient and modern time-reckoning and calendars from around the world.

My posts about Christmas and New Year:

What is the Meaning of the Twelve Days of Christmas?

New Year: Why is it Celebrated?

Christmas Food Traditions: Fast and Feast

Christmas Tree Decorations: History and Symbolism

Christmas Tree: Origin and History

What are Frankincense and Myrrh?

To learn more about northern European mythology read my posts about the Wild Hunt and mistletoe in legends.

Image credits: Featured image – Winter Solstice sunset by fdecomite.

Pin ‘Winter Solstice and Pagan Holidays that Underlie Christmas’ for later