Roman Garden Style and Emperor Nero

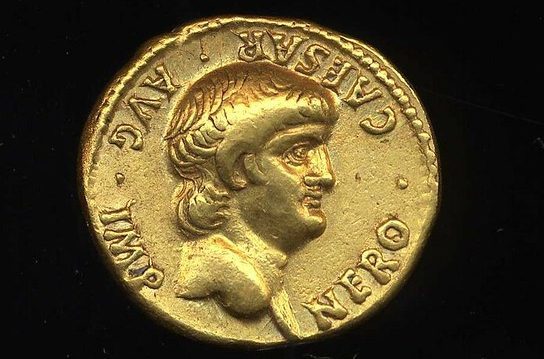

Emperor Nero, the ruler of Rome from 54 to 68 AD, did not create the Roman garden style, but his reign marks a high point in its development. There is no doubt that Nero, the son of promiscuous Agrippina, was a tyrant and a murderer, rightly condemned by almost every historian. But there is one quality that is difficult to deny to him – he really was an artist.

Emperor Nero and the burning of Rome

Rome of Nero’s time consisted of dark and narrow streets, densely packed with tall buildings. They were erected without any plan, each to its owner’s taste. This ugly, ‘formless’, according to the historian Tacitus (Annals, XV, 38), look of the ‘capital of the world’ offended the emperor. It seems that he settled on a radical measure to fix this.

Contemporary sources report, that in 64 AD Nero ordered to start a fire in Rome. The fire, causing countless casualties, was spread by individuals who openly claimed that they had ‘orders’. It raged for about two weeks and burned to the ground two thirds of the ‘eternal city’.

According to Tacitus (Annals, XV, 39), Nero was staying in Antium (modern Anzio) when the fire started, and did not return to the city until the flames reached the imperial palace. He therefore could not have seen the beginning of the fire.

Yet a rumour was persistently circulated that when he saw the flames, he went to the stage of his private theatre and, playing a harp, sang verses about the destruction of Troy.

Rome rebuilt after the fire

Whatever the exact course of events, Nero achieved what he wanted. The massive ruin left by the fire was cleared and the rubbish dumped in the Ostian Marshes. Building started again, but in a different, measured style. The streets were widened, the height of buildings restricted, and open spaces and colonnades were created.

The main building material was stone, resistant to fire. Water was conducted everywhere, and special officials were appointed to oversee that it was available in sufficient quantities for public use.

Nero and Domus Aurea (‘Golden House’)

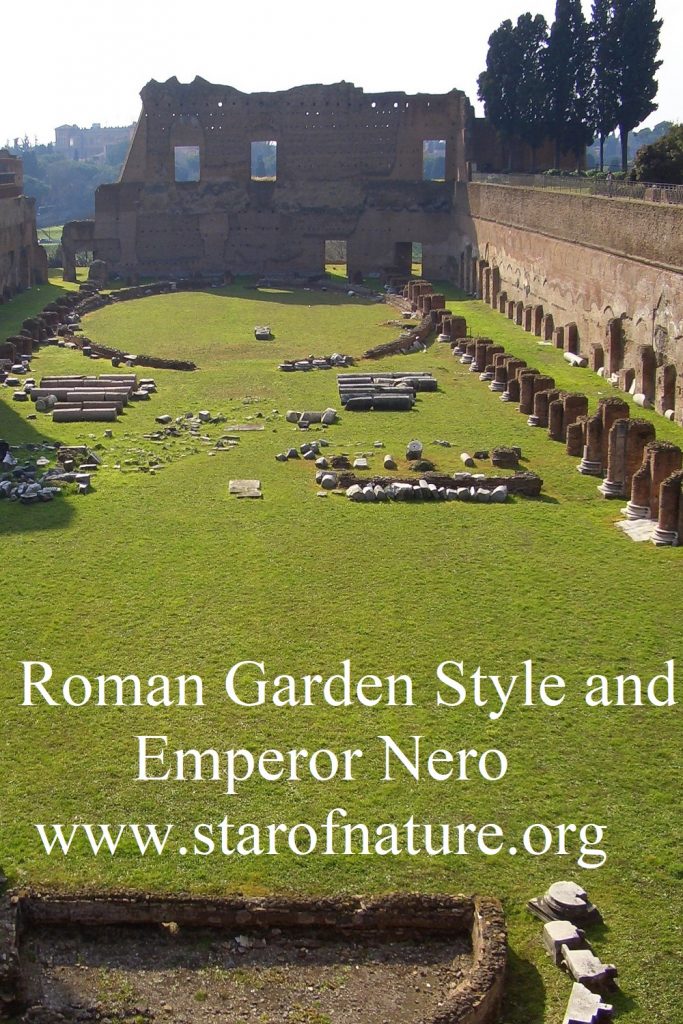

At the same time Nero embarked on another project, possibly the real reason for the fire. Since the emperor’s palace and the surrounding area were destroyed, he started building a replacement. It became known as Domus Aurea (‘Golden House’) due to its lavish decoration.

Domus Aurea was built on a grand scale. According to the historian Suetonius, all parts of it were overlaid with gold and adorned with gems and mother-of‑pearl (Suetonius, Lives, Nero, 31). The dining rooms had ceilings of ivory whose panels could turn and shower down masses of rose petals. They were also fitted with pipes through which guests were sprinkled with perfumes.

The main banquet hall had a circular dome that ‘constantly revolved day and night, like the heavens’. The palace had baths supplied with sea water and sulphur water.

Suetonius reports that when Domus Aurea was finished, Nero uttered no words of approval. He only said ‘that he was at last beginning to be housed like a human being’ (Lives, Nero, 31).

With all its extravagance, Domus Aurea was a treasury of artistic innovation. It continued to influence the European art profoundly for many centuries.

Domus Aurea and artificially created landscape

Both Tacitus and Suetonius also relate that a special landscape was created for Domus Aurea, again on a grand scale. The building work was overseen by two skilful architects, Sever and Celer, who ‘wanted to subdue nature to art’ and were relentlessly spending colossal sums of money (Annals, XV, 42).

In line with their daring plan, the palace was surrounded by tilled fields, vineyards, pastures and woods, with a great number of wild and domestic animals. There was also an artificial lake.

Tacitus points out that this new landscape included special ‘places of solitude’. They were surrounded with forest on one side and offered an open view of a large space on the other side (‘in modum solitudinem hinc silvae, inde aperta spatia et prospectus’). All this was constructed in places that previously did not have anything of this kind.

Controlling nature and attempting the impossible

Sever and Celer even attempted the truly impossible. They offered Nero to connect the lake Avernus with the mouth of Tiber by cutting a passage through a mountain chain. It was expected to be a hundred and sixty miles long, and wide enough for two ships to pass each other!

Nero, ‘with his passion for the incredible’ (Tacitus, Annals, XV, 42), agreed, and the work of digging the stony ground and breaking passes through solid rock commenced. It involved thousands of prisoners and slaves brought from every part of the empire.

Unsurprisingly, the result was a complete disaster. After incalculable expense and a huge amount of effort, the useless plan was abandoned. The results of the ‘mad extravagance’ can still be seen today.

Pseudo-natural landscape and the Roman villa

In spite of all this, the example of Domus Aurea captivated the imagination of Roman aristocracy. The fashion for pseudo-natural landscapes quickly spread. Everywhere for the sake of creating views the land was altered. Lakes were drained, mounds were erected or cut down to the ground, and open fields were planted with forest.

Poet Statius (65-95 AD) tells about these efforts in a poem Silvae. There he describes a villa in Sorrento that belonged to his friend, Pollius Felix:

There was a hill where now is a plain, a wilderness

Where you now shelter; where you see tall trees now

There was once no dry land: the owner has tamed all… («Silvae», II, 2 from Poetry in Translation).

Roman garden style: a triumph of art and a loss of nature

What Nero created in the Domus Aurea, was done in every wealthy Roman house, of course, on a much smaller scale. The main feature of the gardens of that time was an artificially created landscape, that framed a villa.

In the Roman garden style of that period the view was supremely important. Suetonius described this style ‘countryside in the city’ (rus in urbe, Suetonius, Lives, Nero, 31). Though it did not lack grandeur and noble simplicity, it was a triumph of art, not of nature.

Nature was treated rather like a slave to be tamed, and bent to frame the villa that was at the centre of the picture.

Image credits: featured image – the Domus Aurea by William Warby

Posts related to ‘Roman Garden Style and Emperor Nero’:

A Mythological Garden in Odyssey

The Golden Apples of Hesperides

Garden History: What did the Medieval Gardens Look Like?

Medieval Garden Plants and Layout: How to Design a Medieval Garden?

Sweet Violet (Viola Odorata) in History: A Symbol of Joséphine and Napoleon Bonaparte

Review of The Lost Orchard by Raymond Blanc

Pin ‘Roman Garden Style and Emperor Nero’ for later