Wild Salad: Why should we Eat Foraged Greens?

Why should we eat wild salad greens when cultivated salads are so widely available? Foraged edible plants are becoming more and more popular. Many people are trying to learn about wild food by reading about it and attending practical courses. But is it a good idea? Are wild greens any better than cultivated salads?

In my garden I grow a variety of conventional salad greens, such as ‘little gem’, ‘oriental leaves’, ‘lamb’s lettuce’ and other. I very much enjoy them, but I always try to use a mixture of cultivated and wild salad leaves. There are several reasons for this.

1. Wild salad greens taste great

Firstly, there is taste. Eating seasonal wild plants is an opportunity to try new textures and flavours. The problem with many cultivated greens is that they don’t have much taste. Many were bred for large yields and long shelf life, rather than taste.

Another problem is that they don’t change. Eating salads with the same ingredients throughout the year can be boring. This may be the reason why so many people don’t like salad greens. They leave them on their plates when eating in restaurants, as if they are decoration rather then food.

Many wild salad greens, including chicory, dandelion and salad burnet are mildly bitter to various degrees. But so are almost all cultivated salads. I also find that bitterness disappears when several different plants are used.

The trick is

- to use a mixture of different plants, both wild and cultivated

- to chop them finely to allow flavours to mix

- and then add your favourite dressing.

2. Wild salad greens have by far superior nutrient content

Secondly, there is the nutrient content. This is really interesting, and the more you learn about it, the more shocking the picture becomes.

Several studies have found that nutrient content of cultivated plants is now considerably lower than it was in the past. And much of this decline of the nutritional value of vegetables happened in the 20th and 21st centuries. Scientists attribute this to the depletion of soils as a result of intensive farming.

Another likely reason for the drop in nutritional value is the adoption of plant varieties that produce greater yields at the expense of nutritional richness (and also at the expense of taste!).

Decline in the nutritional value of wheat from mid 1960s

Rothamsted Research in Hertfordshire, UK is the home to the oldest continuing agricultural field experiments in the world. Several of their studies started between 1843 and 1856 and are still ongoing.

One of these studies aimed to investigate changes in the mineral content of wheat by using archived wheat grain from an experiment that started in 1843. The study found that the concentrations of zinc, iron, copper and magnesium in wheat

‘remained stable between 1845 and the mid 1960s, but since then have decreased significantly, which coincided with the introduction of semi-dwarf, high-yielding cultivars’ (Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 22, 2008).

Wild plants as superfoods

There are plenty of scientific studies of the nutritional value of wild plants in different parts of the world. Many of them are freely available online. They tend to be full of praise for wild plants as superfood.

Thus, according to P. Stark and co-authors:

‘The nutrient density of 6 abundant [wild plant] species compared favourably to that of the most nutritious domesticated leafy greens’ (‘Open-source food: nutrition, toxicology, and availability of wild edible greens in the East Bay’, Plos One, 2019).

Wild plants as anti-oxidants

S. Datta and co-authors argue that while we need anti-oxidants, synthetic vitamins are not a solution, because they are associated with cancer:

‘The study of antioxidant activity of medicinal plants and vegetables strongly supports the idea that plant constituents can exert protective effects against oxidative stress in biological systems.

The use of synthetic antioxidants … appeared more effective, but continuous usage is associated with cancer and other side effects. Therefore there is an increased interest in the search of natural antioxidant sources’ (‘Nutritional composition, mineral content, antioxidant activity … in some lesser used wild edible plants’, Heliyon 5, 2019).

Wild plants and disease prevention

And according to N. Anjum and co-authors:

‘… studies have shown that edible plants rich in health protective and disease preventive phytochemicals in general, and antioxidants in particular, provide protection against a number of chronic and degenerative diseases’ (‘Wild edibles for nutrition and health’, MFP News 32, 2013).

The conclusion of many scientists is that wild plants are a valuable part of the cultural and genetic heritage of different regions of the world. They played a vital role in human life, particularly as lifesaving food at times of scarcity and natural disasters. Therefore in future wild plants could be nutritious, sustainable and free food, and can increase food and nutritional security.

3. Wild salad greens are convenient

And finally, there is also convenience. Wild plants in the garden are ideal for a busy person as they do not need any care, and are not afraid of slugs, aphids and other voracious wild life. They can be effortlessly grown organically.

Many edible wild plants are perennial and some are available in milder climates all year round. Unlike cultivated vegetables, they do not take your time, and do not require physical work difficult for the sick and elderly.

There is also no expense beyond buying the plant from a nursery initially. Though in most cases even this is not necessary, because the plants are already growing in our gardens. We just need to notice them as our valuable resource.

Some common wild salad greens

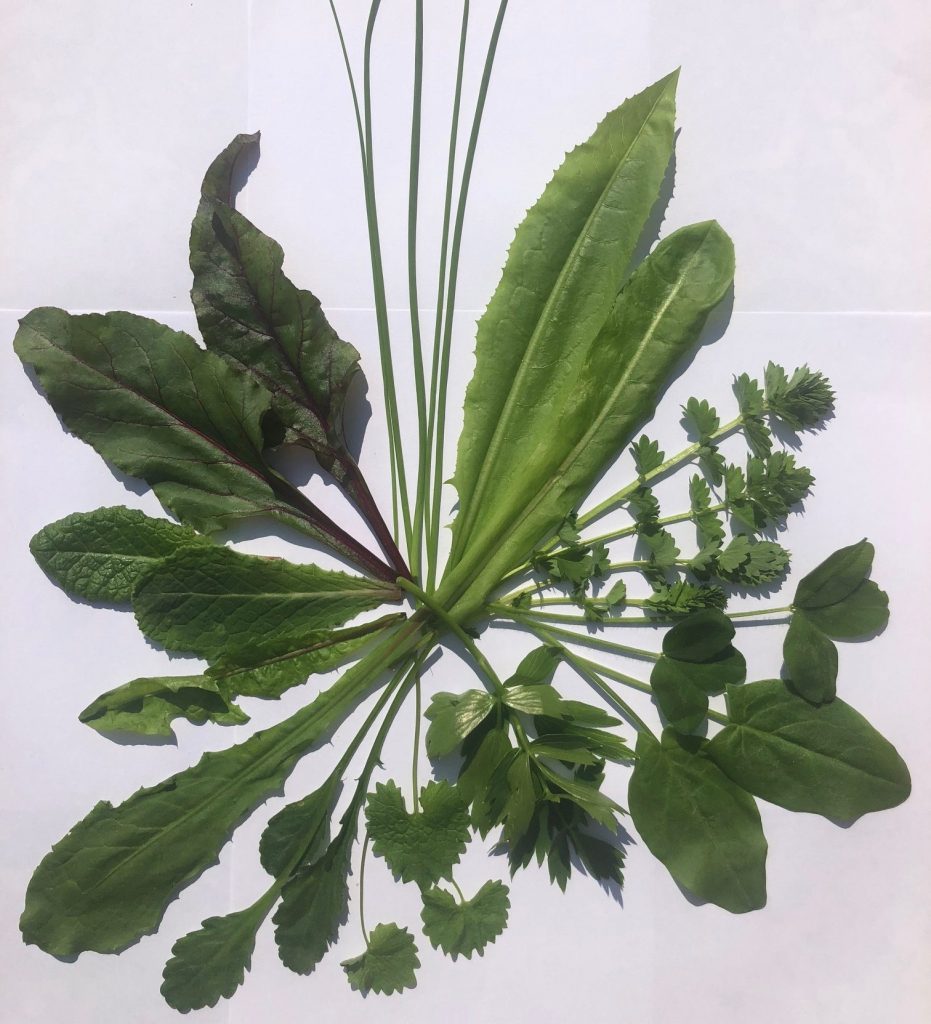

The photograph shows a mixture of plants that grow in my garden in vegetable beds, lawns and borders. I use them most days in salads, from early spring and until late autumn.

Starting at 12 o’clock position, and going clockwise they are: chives, wild chicory, salad burnet, red clover, wild sorrel, lovage, hedge garlic, oxeye daisy, dandelion, primula, beetroot leaves.

This includes only a tiny selection of commonly available wild edible plants.

Learn more about wild salad greens

To learn more about edible wild salad leaves, read the posts listed below.

10 Edible Wild Greens for Autumn and Winter

How to Grow Winter Salad Leaves on the Patio

45 Edible Flowers for Baking, Cakes, Cocktails, Salads and More

Windowsill Salad Garden: Growing Spring Onions

Growing Chicory for Leaves, Flowers and Coffee

Chickweed: A Weed or a Delicious Salad Crop?

Dandelion as a Vegetable: a Beautiful and Useful Gift of Nature

Salad Burnet: Recipes and Growing Advice

Read also my review of ‘Wilding’ by Isabella Tree. She has a chapter on the decline in the nutritional value of food as a result of modern industrial farming practices.

Pin ‘Wild Salad: Why should we Eat Foraged Greens?’ for later