What is the Meaning of the Twelve Days of Christmas?

What are the twelve days of Christmas? Is it a modern invention or an old tradition? And, most importantly, is Christmas entirely over now in early January, after the New Year?

Already in the Middle Ages Christmas was celebrated not as a single day, but as a season that started on the 1st of December and ended on the 6th of January. Today many dislike the early appearance of Christmas decorations and see in it a modern custom driven primarily by consumerism. It is difficult to deny, however, that those who put up their decorations early have a tradition to appeal to.

In medieval church Christmas was preceded by Advent, a special period that began on the 1st of December and was dominated by the theme of prophecy and anticipation of Christ’s birth. Christmas itself closely followed the winter solstice and inherited many features of this earlier feast. The winter solstice celebrations seem to have focused on the rebirth of light, warmth and eventually plants from their temporary death in winter. Considering the importance of the solstice in ancient burial sites, such as Newgrange and Stonehenge, it probably also symbolised rebirth in a religious sense, that is overcoming death in some form.

Christmas too focuses on the themes of light and birth. A passage from chapter 9 of the Book of Isaiah, read at the Midnight Mass at Christmas, announces that ‘people that walked in darkness have seen a great light’. The same verse also hints at overcoming death: ‘they that dwell in the land of the shadow of death, upon them hath the light shined’.

Since solstice cannot be easily observed and in antiquity there was no certainty as to its exact date, festivities dominated by the theme of light occurred at different times in December. This too passed into Christian tradition, resulting in multiple, rather than a single feast. The feast of St Lucy, for example, is celebrated on the 13th of December and focuses on the importance of light: candles, torches, and bonfires are used, as well as wreaths of evergreen plants (and of course special pastries, breads and sweets!). With the arrival of Advent candles are ceremoniously lit in churches and at home, as is still evident in the tradition of Advent candles and wreaths, also combining the symbolism of evergreens and light.

Traditionally Christmas season ended with Epiphany on the 6th of January. The name of this feast derives from the Greek word meaning ‘revelation’ and alludes to a moment when Christ was first revealed to larger world. Epiphany was given different interpretations by different communities, but became particularly associated with the story about the Magi bringing gifts to the infant Christ. The Magi are mentioned in vague terms in St Matthew’s gospel, described as an unspecified number of wise men from the east, bringing gold, frankincense and myrrh. By the 6th century, however, they were re-invented as the three kings from the Book of Psalms predicted to come to honour the Messiah. In some cultures, including Spain and Latin America, gift giving traditionally happens on Epiphany rather than Christmas.

Since there were several important saints’ days between Christmas and Epiphany, in 567 the church council of Tours declared that the whole period of twelve days between the Nativity and the Epiphany formed a single festal cycle. The tradition of the twelve days of celebration following ‘midwinter’ was firmly established by 877, when the law code of the English king Alfred the Great granted freedom from work to all servants during that time.

Epiphany marks the end of the twelve days of Christmas and many families take down their decorations on this day. For some, however, it is also the beginning of a new festive season, the Carnival, that starts at Epiphany in New Orleans, Brazil and the Caribbean. The traditions of the carnival, revelry and misrule were very characteristic of the Christmas period as well, particularly the New Year and Twelfth Night. Both dates were celebrated with all-night parties and temporary inversions of accepted norms of behaviour, social hierarchy, power and status, and everything normal, conventional and stale.

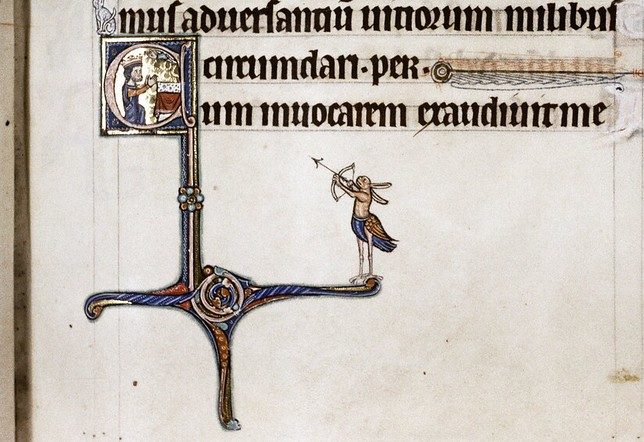

In the Middle Ages the 1st of January was celebrated as the Feast of Fools, initially in northern France, then more widely in Europe, including England. It was led by junior clergy who temporarily usurped the roles of their superiors and performed parodies of religious services and processions wearing masks, women’s clothing, fools’ costumes, garlands and wreaths. They did everything that was normally inconceivable in religious buildings, including dancing, running and leaping through the church, singing ‘unchaste’ songs, playing dice and, according to a testimony from mid-15th-century France, even eating black pudding on an altar and using smoke from the soles of old shoes instead of incense.

Such celebrations were disapproved of by many and eventually prohibited by the church. For someone sufficiently open-minded, however, the reversal of power has a religious justification: after all Christ elevated the humble.

An earlier difference between Christmas and New Year, with Christmas being primarily religious and New Year displaying strongly secular tendencies, continues in a different form today. Christmas focuses on family, tradition, authenticity, medieval and Dickensian past, and is associated with nature, rural settings, snow-covered fields and woods, quiet villages and crackling fires. New Year is on the contrary urban, modern and is associated with revelry, glamour, glitter and firework displays.

Ultimately, however, neither feast can escape the connection with nature and its cycles. Winter celebrations, the whole twelve days of them and more, became particularly important in northern countries where cold, darkness, isolation and desolation of midwinter are felt particularly strongly. In southern Europe Christmas is overshadowed by Easter. Winter holidays is a seasonal celebration that we very much need, particularly those of us living in the north. Having said this, the importance of light, birth and rebirth, asserted by midwinter celebrations, is a theme that no human can ignore.

See also: Larsen, Timothy (ed.) (2020). The Oxford Handbook of Christmas. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Related posts:

Christmas Tree: Origin and History

New Year: Why is it Celebrated?

Christmas Food Traditions: Fast and Feast

Winter Solstice and Pagan Holidays that Underlie Christmas

Christmas Tree Decorations: History and Symbolism