Growing Lily-of-the-valley in Winter

Lily-of-the-valley (Convallaria majalis) is an undemanding woodland perennial often grown as a decorative plant. It is found in the wild in Europe, Asia and North America. Though it naturally flowers in May, there is a long tradition of growing lily-of-the-valley in winter. In fact forcing it indoors in pots was a big industry in the 19th century.

Symbolism of lily-of-the-valley

For many lily-of-the-valley is an emblem of spring. In the 19th century it was a favourite flower to grow for Easter. It often appears on Victorian postcards as a symbol of beauty and youth, though sometimes also of mourning.

In the second half of the 19th century it was overwhelmingly fashionable as a design motive, and used on jewellery, pottery and fabric. Lily-of-the-valley perfume, sadly rare today, was a great favourite.

Lily-of-the-valley in winter: 19th-century traditions

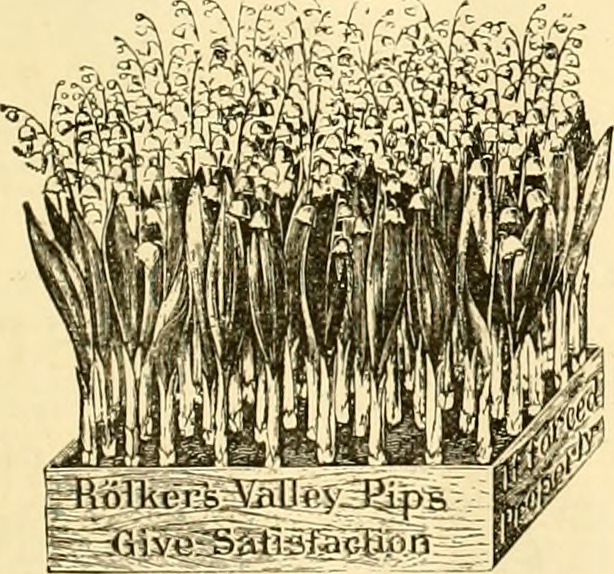

What is somewhat unexpected, is that lily-of-the-valley also appears on Victorian Christmas cards. This is due to a once common art of forcing it in winter. Roots were sold by florists in late autumn for growing indoors. And pot-grown flowering plants were on sale at Christmas and in early spring, long before their natural flowering time in May.

Growing lily-of-the-valley in winter is uncommon today, perhaps because it requires more effort than hyacinths and daffodils. Hyacinths and daffodils, by the way, were also popular as Christmas and Easter flowers in the 19th century, but, unlike lily-of-the-valley, they kept their popularity.

Considering the present-day rarity of lily-of-the-valley, its exquisite beauty, lovely smell and nostalgic Victorian appeal, it seems to me that it is worth trying to grow it in winter, if appropriate conditions can be created.

Forcing lily-of-the-valley in winter

I have done some research in 19th-century gardening books and this is the advice I found.

Selecting roots

The most important first step is to select strong and healthy roots. They can be bought from florists or dug out from the garden.

The roots should not come from plants previously forced in pots in winter – they will not be strong enough to produce good flowers. The choice of roots is crucial: the strongest and thickest rhizomes need to be selected, with healthy buds on top.

It is also important to select rhizomes with the right buds. They should be the flower buds, not the leaf buds. The buds that will produce flowers are rounded on top and point upwards, away from the root. They should not be confused with pointy horizontal buds that will produce only leaves.

Before planting, cut the rhizome into segments 7-12cm in length, leaving all thin side roots intact.

Planting lily-of-the-valley in pots

The roots should not be dug out before the beginning of October. If they were acquired earlier, they need to be kept in the garden in boxes with compost or sand.

In October plant them in pots. The pots don’t have to be particularly deep and can be any width. For example, 5 or 6 rhizome segments can be arranged in a circle in a pot 15-20cm in diameter.

Put drainage, for example, pieces of a broken pot, at the bottom of a container. Fill the container with compost. The soil should be soft and ideally rich in organic matter, similar to the soil on wood floor.

Though the plants will develop using nutrients stored in rhizomes, richer soil will help leaves to grow well after flowering. As a result you will be able to keep the plants and grow them in the garden. Some gardeners recommend adding chopped moss to the soil.

Place the rhizome segments on the surface of the soil, 1-3cm away from one another and not touching. Cover with 0.5-1cm of soil, so that the tops of the flowering buds are just above the surface.

Exposure to frost

Keep the pots with planted roots outside. It is important that they catch a frost. Ideally the compost in the pot should get frozen throughout. This may be difficult to achieve in areas with mild winters, but it is essential.

For commercial growing 7-10 days at -5C is recommended, but old gardening books suggest that one exposure to a frost of around -5C is sufficient. After exposure to frost pots can be transported to a cellar, shed or garage, and left without watering.

Transporting lily-of-the-valley indoors

Forcing lily-of-the-valley differs from growing of other plants out-of-season. Whereas for other plants the temperature is increased gradually, for lily-of-the-valley it should be increased suddenly and dramatically. Therefore, instead of putting the pots in a cool greenhouse or a room, transport them straight into heat.

If they can be started at a temperature of 25-35C, it is possible to bring them to flower in as little as three weeks. Though this depends on individual conditions, and 25-40 days may be necessary.

It is therefore important to decide when it is desirable to have flowers. Plants that should flower at Christmas, need to be transported into warmth in late November or early December.

Growing lily-of-the-valley indoors

During the initial stages of growth the plants need to be kept in darkness. Considering this and the required high temperature, a propagator may be the only practical solution.

To start the plants into growth, water them with warm water. And to create a natural look, put moss around the flower buds just visible above the soil.

If you have a propagator, put the pots in a propagator and keep them moist, dark and at a constant temperature of 20-35C (the ideal temperature is 25C or above).

Alternatively put the pots somewhere where even heat can be maintained, for example, on or next to a radiator. Ideally the pots should be heated from underneath. To achieve this keep them on a surface warmed to 25-35C by a radiator or other heat source.

For example, put the pots in a waterproof tray, constantly filled with a little water, on top of a radiator. If the radiator is too hot, put something under the tray, for example, a piece of wood, a brick or a ceramic tile.

Cover the pot with another clay pot of a similar size with a bottom hole blocked to maintain heat, humidity and darkness.

Looking after plants when shoots appear

Once the shoots start appearing, unblock the opening at the bottom of the covering pot to let the air in. As the shoots grow, and not long before the flower stalk appears, lift the covering pot slightly above the soil by inserting supports under its edges. Small stones or rolled pieces of newspaper can be used as supports. This will allow more air to flow to the shoots.

Once the flower appears, remove the pots used for covering, and transport the plants to a bright cool (16-21C) windowsill.

A bright position is important. For commercial growing artificial light is recommended – 3 hours in the morning and 3 hours in the evening to increase daylight to 12 hours.

Exclude the drafts and keep the compost moist.

After the end of flowering, later in spring, plant lily-of-the-valley in the garden and leave for 2-3 years before forcing it in winter in pots again.

Lily-of-the-valley: meaning

The Latin name of lily-of-the-valley, Convallaria majalis, derives from convallis – ‘valley’ and majalis – ‘of May’.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the English name, lily-of-the-valley, is a literal translation of Latin (Vulgate) biblical lilium convallium (‘lily of the valley’). In the Old Testament this phrase appears in the Song of Song (2:1): Ego flos campi et lilium convallium (‘I am the flower of the field and lily of the valley).

We don’t know exactly which flower is mentioned in the Song of Song. The application of this name to lily-of-the-valley is apparently due to the German herbalists of the early 16th century.

Lily-of-the-valley in the language of flowers

In the language of flowers a bunch of lily-of-the-valley meant ‘I loved you secretly for a long time’.

How to grow lily-of-the-valley in the garden

It is best to grow lily-of-the-valley in partial shade. It should not be deep shade, however, where it will not flower well.

Lily-of-the-valley can survive draught, but it prefers relatively moist soil, rich in organic matter. Neutral soil is ideal. To get the best flowers, mulch the soil with compost in August.

Lily-of-the-valley is very hardy and does not need protection in winter.

Is lily-of-the-valley poisonous?

Lily-of-the-valley is toxic rather than poisonous. All parts of it contain substances that have activity on the heart muscle. They are toxic to humans if eaten. The same substances, however, are medicinal when used correctly and in small quantities.

Lily-of-the-valley is certainly not as hazardous as some highly poisonous plants we encounter in everyday situations. It is nothing like the beautiful but extremely poisonous monkshood, that is widely sold by florists and grown as a decorative plant in gardens. It is certainly not dangerous to touch lily-of-the-valley.

Of course a degree of caution makes good sense. Even water in which the flowers stood can be harmful if drank, so it should be kept out of the way of children and pets. But there is not need for any special precautions.

Lily-of-the-valley was used as medicine, primarily for heart conditions, since antiquity. It is still grown commercially for the pharmaceutical industry.

Image credits: ‘Lilly-of-the-Valley’ by Kaarina Dillabough; ‘Lilies of the Valley’, Albert Durer Lucas by Irina (Flickr), Lilly-of-the-Valley on a postcard by plaisanter~, image from ‘The American Florist’ from Internet Archive Book Images, pin – Charles D’Albert (1809-1886), ‘Lily of the valley: valse a deux tems’, Jerwood Library of the Performing Arts.

Posts related to ‘Growing Lily-of-the-valley in Winter’

Sweet Violet (Viola Odorata) and Parma Violet: How to Grow Forgotten Treasures

Reblooming Amaryllis: Two Ways to Grow Amaryllis Bulbs Indoors

Autumn crocus (Colchicum autumnale) – a Star of Early Autumn

Indoor Garden Ideas: Growing Microgreens on a Windowsill

Pin ‘Growing Lily-of-the-valley in Winter’ for later