Garden History: What did the Medieval Gardens Look Like?

Medieval gardens were orderly spaces where beauty coexisted with utility. Gardeners of the Middle Ages developed essential skills and learned to grow edible, medicinal and decorative plants that are still indispensable to us today. In this post I explain who the medieval gardeners were, what was in a medieval garden, and what the gardens of this period looked like.

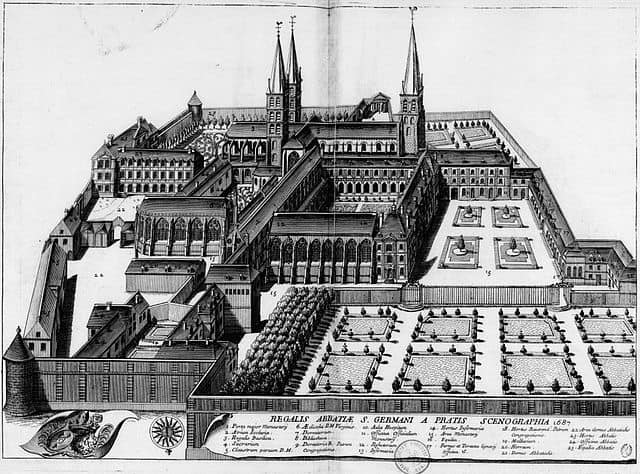

Monastic gardens: medieval garden layout

Monasteries were not only the centres of literacy in the Middle Ages, but also of medical, agricultural and culinary knowledge. To practice all these skills monks needed gardens, and so monasteries became the hubs of botanical learning and gardening know-how.

Being literate, monks also knew more about the ancient Greek and Roman culture than other classes of society. As a result they seem to have preserved some principles of the classical gardening style, first of all symmetry.

The medieval garden layout was strictly geometrical. Paths and alleys crossed at right angles, and flower and vegetable beds were laid between them in measured, symmetrical patterns.

Symmetry was not only an expression of beauty, but also of order, discipline, tranquillity and seclusion. Monasteries were places of prayer and meditation, and so harmony and calm were essential psychological states that the gardeners aspired to capture.

Monastic gardeners also favoured practical utilitarian approach. They creations had to serve human needs as well as divine. The gardens of the Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino in Italy, established in 529, were planted with medicinal and edible herbs, as well as simple fruit trees and grape vines. The monks also grew roses, lilies and different vegetables since the skill of cultivating these plants survived from the time of the Roman empire.

The art of gardening that developed in Italian monasteries soon crossed the Alps. The monasteries in France and Germany, such as St Gallen, Clairvaux and Wezelay, also became famous for their gardens. In 820 the garden of St Gallen, in line with the principles of balance and utility, was subdivided into 16 symmetrically positioned beds where lilies and roses flourished next to the medicinal and culinary herbs, such as sage and dill.

Read more about the layout and plants of medieval gardens: Medieval Garden Plants and Layout: How to Design a Medieval Garden?

Royal medieval gardens: Charlemagne

Since Christianity had such a dominant role in the life of the medieval society, monasteries had close connections with the royal courts. Monastic gardens influenced royal medieval gardens.

A particularly prominent figure in the development of medieval gardening was Charlemagne (768-814). This energetic king established his own gardens in Ingolsheim and Aachen, and supported monastic and private gardens in his lands.

Due to his friendly relations with Caliph Harun al-Rashid (modern Iran, 766-809), he introduced many new vegetables and fruit to Germany and France. These included different varieties of beans, melons, figs, peaches, and many other agricultural plants still grown today.

Early medieval Germanic law codes, such as the early 7th-century Lex Alamannorum, do not mention gardens or plants. A somewhat later Bavarian law code of 741-748 (Lex Baiuvariorum) already has a section on orchards, forests and bees that names different varieties of apples and pears. But Charlemagne gives a full list of what was growing in his gardens in section 70 of his Capitulare de villis, a document that guided the governance of the royal estates. The list includes:

- medicinal plants, such as mallow, rue, elecampane, marshmallow, sage, mint, oregano, thyme and coriander

- decorative plants, such as white lily, rose and, interestingly, rosemary

- vegetables, such as beans, peas, cabbage, turnip, beetroot, onion, shallot, leek, garlic, celery and parsley

- orchard trees, including different varieties of pears, apples, plums, peaches, quinces, hazelnuts, Cornelian cherry and mulberry.

This botanical section of Capitulare de villis was based on book 10 of De re rustica (‘About rural matters’), an influential work of a Spanish gardening expert Columella who lived in the 1st century AD. Columella was apparently the first to advise to cover cucumbers and melons with frames during the cold seasons of the year.

Gardening style that developed under Charlemagne was not purely, but mostly utilitarian. The gardens considered to be the best were the ones that contained the largest number of useful, particularly rare and medicinal plants.

*Read more about elecampane: Elecampane (Inula helenium): Ancient ‘Sunflower’ of Europe

Medieval gardening manuals

The first literary work of German gardening was De Universo (‘On the universe’) of the famous monk and abbot Hrabanus Maurus (about 780-856). In this encyclopedia he describes the qualities, use, and symbolic and spiritual meaning of around 100 plants. These are the plants that are either mentioned in the Bible or were commonly grown in the gardens of his time.

Hrabanus’s student Walafridus Strabus (807-849) wrote a poem Hortulus (‘Small garden’) where he described 23 plants that he grew in the garden of Constanz monastery.

Macer Floridus, who lived at the end of the 9th century, wrote a poem De viribus herbarum where he described 77 plants including elecampane, lemon balm and sorrel.

The next important work on gardening was by Hildegard (1099-1179), abbess of Bingen. She described several plants that were unknown or rare under Charlemagne, including Citrus medica – lemon. Lemon was rare in ancient Roman gardens, but became popular in the Byzantium.

Among plants described by Hildegard are marshmallow, primrose, peony, pulmonaria, calendula, catmint, cyclamen, watercress, radish, cabbage, blackthorn, blackberry, blueberry and many other.

Albertus Magnus – medieval gardening expert and magician

Probably the most prominent figure of learned medieval gardening was a German Dominican friar Albertus Magnus (1193-1280). He had a reputation as a philosopher, scholar and a magician. In 1260 he was made the bishop of Regensburg, but returned to his monastery in Cologne to pursue science.

There he wrote a book on gardening De vegetabilibus (‘About plants’) in which he describes 170 plants. These include aquilegia, catmint, 5 varieties of rose, rice, box, fig tree, olive, almond, peach, quince, sweet chestnut, apple, cherry, grape, black, green, red and yellow plums and many other. Albertus explains how to grow the plants, including what he believes to be the influence of planets on their development.

Albertus seems to have established hot houses in his garden. This is suggested by a story of how he entertained king William II of Holland. The king visited Albertus on 6 December 1249. Albertus invited him to dinner in his garden where everything was green and blossomed, as if it were the middle of the summer, rather than deep winter. Clearly the dinner was served in a winter garden.

In his book Albertus writes about grafted plants. Some things he says are rather curious by modern standards. He explains, for example, that a rose grafted on a cabbage will produce green flowers without scent. He also complains that he did not have an opportunity to find out whether roses will flower in winter in cool conditions if watered with human blood (!).

Utilitarian and pleasure gardens

In 1305 Petrus de Crescenziis, a Bolognese jurist, wrote a book Opus ruralium commodorum (‘Book of rural benefits’). It was printed in 1471 in Augsburg. It was very popular in the 15th century as a practical treatise on the planning and cultivating a country estate. Petrus was the first to classify the gardens into utilitarian and those for pleasure.

In part 8 of this 12-part book he subdivides the pleasure gardens into three types, according to the owners’ wealth. All three types should be decorated with lawns, scented flowers and small trees. Royal pleasure gardens should have in addition to this enclosures for birds and animals.

The Rose of Hildesheim

Gardening became less utilitarian and developed a stronger decorative trend in the second half of the 11th century. The leaders here were again monastic gardens, including Clairvaux, Wezelay and St. Gallen. They were highly praised by prominent figures of the time for their beauty, as well as usefulness.

One decorative feature from this period still survives. A dog rose (Rosa canina), widely known as a Thousand-year Rose, grows around on the apse of the Hildesheim Cathedral. It is documented to be at least 700 years old and is probably much older.

According to a legend it was planted in 815 by the cathedral’s founder Emperor Louis the Pious, the son of Charlemagne. The cathedral was completely destroyed during the Second World War and rebuilt in 1950s. The roots of the rose survived the bombing and it regrew. Today it grows perfectly well and reaches a height of around 10 m.

Medieval castle gardens

Feudal medieval gardens were smaller than royal and monastic gardens. They were planted in enclosed spaces – it would have been too dangerous to have them outside the castle walls because armed conflicts were common. In the early Middle Ages even woods were not tolerated next to castles and fortresses for fear of an ambush.

Nevertheless, gardens were planted in castles whenever possible. They contained both flowers and vegetables and were laid out symmetrically. A famous French medieval poem Roman de la Rose describes a green garden (‘jardin tout vert’), surrounded by a strong and tall wall. It has a square shape (‘it was long as it was wide’) and is planted geometrically. The garden is filled with fruit trees, positioned symmetrically, at equal distances from one another, and there are neatly trimmed green hedges. The garden also has flowers in different colours, including particularly beautiful red roses, and a fountain.

French royal medieval gardens

The gardens of the French king Charles V (1338-1380) were in Saint-Paul area, part of the modern Marais district in Paris. There the king planted a large cherry plantation – he bought 100 cherry trees for 5 sous. The garden also had roses and lilies, and 8 laurel trees.

This garden was redeveloped at the time of the Hundred Years’ War between England and France. In spring 1431, during the trial of Joan of Ark, it belonged to Duke of Bedford, English prince and general. He commanded England’s armies in France and put Joan on trial by pro-English clergy.

Bedford ordered to dig a trench about 2000 metres long next to the Château de la Tournelle, a now-demolished castle that was on the left bank of the Seine at the centre of Saint-Paul area. He planted the trench with 5913 elms and filled with fruit trees the garden inside. To them he added, as decoration, 31 holly trees and several blackthorns. Five years later the garden passed back to the French king Charles VII, as the English suffered defeats and were gradually expelled from France.

English medieval gardens

Scottish king James I (1394-1437) spent several years as a prisoner of the English king Henry V (1413-1422). He described the royal garden at Windsor Castle in one of his poems. He wrote that the garden was surrounded with a stone wall with turrets and planted with trees, flowers and herbs. It had lawns and was transacted by long narrow paths flanked with hawthorn hedges.

Poet and historian John Leland (1503-1552) wrote in his ‘Itinerary’, notebooks on his travels in England, about several large gardens. He gives particular attention to Wressle Castle in Yorkshire. He explains that it had a flower garden inside the castle walls and a fruit garden outside. The fruit garden has mounds with steps going up them in a spiral.

Merchants’ gardens

In the later Middle Ages, as the middle class was becoming more influential and powerful, it became common for wealthy merchants in Augsburg, Regensburg, Nurnberg and other large towns in Germany to have their own gardens. The gardens were planted with white and red roses, lilies, violets, crocuses, pinks and carnations, as well as medicinal herbs and vegetables.

The layout of such private gardens was very simple. They were transacted with several straight paths leading to small gazebos. Between the paths were symmetrically positioned beds planted with flowers, small trees and vegetables. Exotics, found in particularly wealthy gardens, were lemon and laurel trees, and rosemary.

In spite of their simplicity the gardens were highly valued. There were cruel punishments to those who damaged them. According to Landfriedensgesetz of 1187, anyone who damaged a grafted fruit tree was subjected to mutilation. Later laws introduced perpetual exile in addition to mutilations.

At the end of the 15th century gardens experienced a radical change. It followed the discovery of America (1492) and of the route to Ost-India. Merchants, who became wealthy as a result of trade that these discoveries made possible, established luxurious gardens. These gardens were stocked with exotic plants, such as American aloe and Syrian hibiscus.

German gardeners particularly excelled in the 16th century, developing many new varieties of fruit trees. By the middle of the century they knew 50 varieties of pear. Gardening became so prestigious that in 1415 it was declared one of the ‘liberal arts’ in Augsburg. In the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century gardeners in Germany had the right to wear a sword.

Medieval beliefs about plants

In spite of the achievements of the scientific study of plants, popular beliefs about them flourished in the Middle Ages. Plants were commonly used as amulets. People believed that St John’s wort protected against thunder and ghosts, reseda attracted a lover, whereas daisy cured love sickness.

But the most important role in magic was given to mandragora – Mediterranean plant Mandragora officinarum. It was used for all kinds of sorcery. Around 1500 monks in Germany cut male or female figures from it and sold for a princely sum of 30 gold guldens.

Image credits: featured image – cloister garden next to the Dom church in Utrecht by Bart van Leeuwen; Abbey Saint Germain des Prés in 1687 – WikiCommons; medieval garden, Cahors Cathedral, Lot, France by Phillip Capper; medieval garden at Ermenouville, Seine Maritime, France by isamiga76; the Rose of Hildesheim by Ashley Van Haeften; mandragora officinarum by Candiru.

Pin ‘Garden History: What did Medieval Gardens Look Like?’ for later

Posts related to ‘Garden History: What did Medieval Gardens Look Like?’

Medieval Garden Plants and Layout: How to Design a Medieval Garden?

Roman Garden Style and Emperor Nero

A Mythological Garden in Odyssey

The Golden Apples of Hesperides

Sweet Violet (Viola Odorata) in History: A Symbol of Joséphine and Napoleon Bonaparte