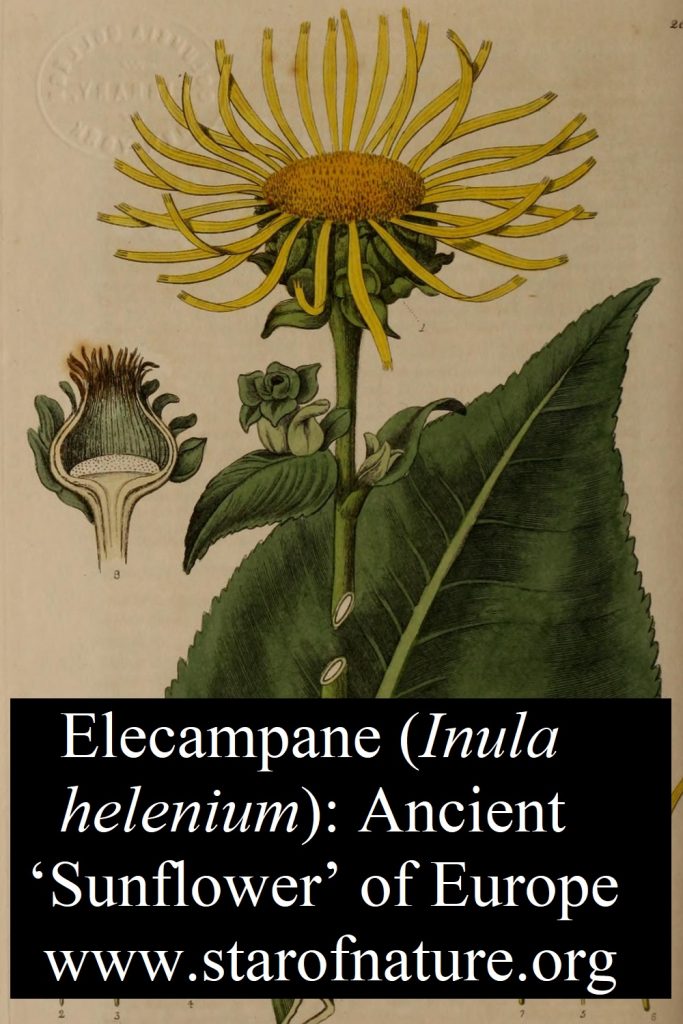

Elecampane (Inula helenium): Ancient ‘Sunflower’ of Europe

Elecampane (Inula helenium) is a perennial flowering plant from the aster family. It is native to Europe and Asia, and naturalised in North America.

Origin of the Latin and English name

Its Latin name, Inula helenium, is derived from Greek inaein (‘to purify’) and helios (‘sun’), reflecting its medicinal use and sunflower-like appearance.

It’s exotic sounding English name is a corruption of medieval Latin enula compana, where campana may mean ‘Campanian’ (from Campania, region in Italy) or it may have the sense ‘of the fields’.

Growing elecampane

Elecampane is typically 100-200cm tall and highly decorative. It flowers for a long time in July and August, and is much visited by bees.

Its height, multiple large yellow flowers and robust thick fluffy stems make it a dramatic ‘statement’ plant for the garden. Its large impressive leaves are dark green on top and grey and downy underneath. It looks exotic and powerful.

It prefers full sun and deep, rich and relatively moist soil. As a wild flower, however, it is generally undemanding and easy to grow. It flourished in my garden in spite of a very dry spring and hot summer of 2020.

Growers give conflicting recommendations as to the hardiness of inula helenium. To my best knowledge it is hardy to below -20C (zone 5). It prefers continental climate with hot summers and cold winters.

In my garden I grow it in a border next to other tall plants. It looks wonderful both when planted in groups and as a single statement plant.

I have also seen it grown in sunny wild flower lawns. It looks very effective next to grasses and other wild flowers. And it will do well in such conditions as long as the lawn is mowed once a season, in autumn (September of later), when plants are about to go dormant.

Elecampane’s traditional English names, ‘horse-heal’ and ‘elfdock’, suggest that it was once a common wild flower in Britain. The more often it is grown in wild-life, as well as formal gardens, the more likely it is to return and grow in meadows once again.

Propagating elecampane

Elecampane is not very commonly grown today, but it can be bought as a potted plant from nurseries. Be somewhat careful, however. Some nurseries seem to be selling species of hellenium as inula helenium, presumably because of confusion. But they are completely different plants, in spite of the similarity of their names.

Though many early authorities, starting with Pliny, say that its seed is ‘superfluous’, elecampane can be easily grown from seeds. Sow the seeds direct in spring (March) or autumn (September). In its first year it will produce only leaves, but it will flower in its second year.

It can be also propagated by dividing roots – indeed, if the roots are harvested (see below), it is best to replant smaller pieces.

Elecampane benefits and use in medicine

There are numerous ancient, medieval and modern recipes where elecampane is used for the treatment of serious illnesses. These include cancer, tuberculosis, cough and bronchitis, allergy, neuroinfections, digestion disorders, high blood pressure, rheumatism and old age sclerosis.

Elecampane is also used in the form of baths and compresses to treat skin disorders. It even inspired several medical discoveries. Thus, inulin, a white starchy substance, was first extracted in 1804 by a German scientist Valentin Rose from the roots of elecampane. Today it is mostly extracted from chicory roots and used as a dietary fiber.

Elecampane’s English names, such as ‘horse-heal’, also reflect its prominence in veterinary medicine. It was once used to treat respiratory infections, digestion disorders and wounds of domestic animals.

Elecampane in mythology

Some of elecampane’s names, such as English ‘elfdock’, suggest that it was once important in myth and ritual. It was probably sacred to many peoples of Europe and Asia.

There is a legend about its connection with Helen of Troy, mentioned by the Roman naturalist Pliny (23/24-79 AD) and numerous later authors:

‘Helenium is said to have sprung up from the tears of Helen, and therefore is very popular in the island of Helene’ (Natural History, XXI:XXXIII, Loeb Classical Library, 392).

Inula britannica

There many other plants belonging to the inula genus. Several of them are also used in medicine, though much less extensively than elecampane.

Perhaps the best known of these is Inula britannica. It is a much smaller plant with yellow flowers, still very common in Britain. In the past it was occasionally used in bread-making instead of yeast.

Elecampane root

Elecampane is one of the most important plants in traditional European, as well as Chinese and Tibetan medicine, where mostly roots are used, though occasionally also leaves.

The roots are collected in autumn or early spring before the growth starts. They are then washed, diced and dried at a temperature no higher than 40C. The root can be kept for up to three years without loosing its properties.

Finely chopped or powdered roots are used in water, oil and alcohol infusions, often in combination with other plants, particularly burdock. They can be bought from health stores or online.

The roots have a strong smell, similar to camphor when fresh, and similar to violet when dry. They have a bitter, pungent taste. Elecampane root can be used as a spice to flavour fruit and vegetable dishes.

Elecampane recipes: wine

Many earlier authors give recipes of elecampane wine and recommend it as a medicine and tonic for those recovering from an illness. Avicenna in The Canon of Medicine (Canon of Medicine by Hakim Ibn-Sina, 2:iv, 223) says:

‘It belongs to a class of drugs which are attenuant and strengthening for the heart. The method of its application is that 50 mithqal (225 gm) of elecampane is mixed up with six obolusat (36 gm) of grape juice and kept. It should then be taken after three months. This method of application clears the lungs and chest.’

Here is a modern version of this recipe (given with some variations by different authors).

Elecampane wine is made from fresh root, so it can be prepared only in autumn or early spring before the plants start to grow.

Add 1.5 tablespoons (or 12g) of very finely diced root to 0.5 litre of dry white wine. Bring to boil and boil gently for 10 min. Cool and store in a dark cool place. Take 1 tbs (or up to 50g) twice a day.

Elecampane should not be taken in pregnancy, and by those with kidney and cardio-vascular disorders. It can cause allergic reactions in some if used for prolonged periods of time.

Elecampane recipes: porridge

Ingredients: 300g of oats, 75 fresh elecampane root or 20g dried root, 600g milk, 300g water, optional 1 tbs honey, or fruit compote, or salt to taste.

Add oats to a boiling mixture of water and milk. Add root. Finally, add salt, if desired. Cook on light heat till the porridge is ready (for cooking time follow the instructions for the porridge oats you are using).

When serving add 1tbs of honey or fruit compote, if desired.

I love this recipe. I use dry powdered root and just water, though sometimes I pour a little cream on porridge before eating.

Cosmetic oil with elecampane

Boil 4 tablespoons of finely chopped dried root in 200ml of vegetable oil for 15 min. Keep in a tightly closed (dark) glass jar in a dark place for 1 week. Strain and keep in a dark cool place.

To clean the skin, put the oil on the skin for 1-2 min, then remove with a moist cloth. The oil reduces inflammation and dryness, and has healing and antimicrobial properties.

Image credits: featured image – Elecampane (Inula helenium) by Tom Parnell; Elecampane by Len Worthington

Related posts

Garden History: What did the Medieval Gardens Look Like?

How to grow wild flowers in the garden

Growing Chicory for Leaves, Flowers and Coffee

Dandelion: a Beautiful and Useful Gift of Nature

Pin ‘Elecampane (Inula helenium): Ancient ‘Sunflower’ of Europe’ for later