Sweet Violet (Viola Odorata) in History: A Symbol of Joséphine and Napoleon Bonaparte

Violets had a truly amazing and very strange role in the life of the French Empress Joséphine and her husband Napoleon Bonaparte. They became a symbol of their love and a political emblem of Napoleon’s supporters. Many fascinating stories about violets and the imperial couple, and even about the flower’s role in the fate of their descendants, are told by contemporaries and historians of that turbulent time. Some are probably legends, but they reflect the spirit of the epoque and its enchantment with the violet. A few are therefore related below.

The story begins on the 9th of March 1795. Late in the evening, as we learn from the testimonies of some contemporaries, a young beautiful lady with a pot of luxurious violets appeared at the gate of the prison Temple. The prison was where the Dauphin, Louis XVII, the son of the executed King of France Louis XVI and Queen Marie-Antoinette was kept. He was only 10 years old, isolated, mistreated and ill with tuberculosis. The lady asked the guards to give violets to the child who apparently loved the flower.

The lady was Joséphine de Beauharnais, the future French empress. She loved violets too, and felt pity for the imprisoned child. She was thought of as kind and generous by her contemporaries, and probably believed that a glimpse of spring will give the Dauphin some hope and consolation.

Joséphine was well aware of the dangers that could result from such an act of kindness. She came accompanied by a powerful friend Paul Barras, one of the five members of the Directory, the governing body of the French Republic. Some contemporaries claimed that Joséphine wanted to save the Dauphin, and to please her Barras was planning his escape.

But the poor child did not outlive their visit for long. In June of the same year he died in prison, apparently badly neglected and devoid of human contact. He was buried in the graveyard of the church of Sainte Marguerite. No memorial was erected, but there is a legend that some kind soul planted violets on his grave. They gradually entirely covered the burial place, producing a carpet of purple flowers each spring.

Meanwhile at a ball, hosted by Barras, Joséphine met young general Napoleon Bonaparte. She immediately charmed him with her beauty and modest outfit that contrasted to those of the ladies of the republican high society. Instead of gemstones she wore a garland of violets on her head and a posy of violets on her shoulder.

Apparently, Joséphine loved violets because they reminded her of her own lucky liberation from prison. In January 1794 she was arrested together with her first husband, Alexandre de Beauharnais, and imprisoned in the famous Conciergerie in Paris. Her husband, a general of the republican army, was accused of military failures and executed. Joséphine expected to follow him to the guillotine, and lost all hope, when apparently one evening a little daughter of one of the guards came to her cell and gave her a bunch of violets.

Joséphine took this as a good sign. She knew that one of her high-ranking friends was doing everything she could to save her. She was indeed freed the next day. This was only a few days after the deposition and execution of Maximilien Robespierre, the President of the National Convention. His death put an end to the Reign of Terror, established by the revolutionary government, and many prisoners were released.

For Joséphine violets because a symbol of a happy turn in her life. Her attachment to them was exceptional. They were embroidered on her dresses. Lilac was one of her favourite colours. Bunches of fresh violets were her much loved decoration.

On 9 March 1796, apparently exactly a year after she brought violets to the Dauphin, Joséphine married Napoleon in the town hall in Paris. She was dressed in a gown embroidered with violets, and said that she wanted to see and wear violets always on anniversaries of their wedding. Napoleon took this request to heart and made it a tradition that he observed religiously. Wherever he was, whether abroad or fighting in a military campaign, he always had a bunch of fresh violets delivered to Joséphine on their wedding anniversary.

Several years passed. Joséphine became an Empress. On the occasion of her coronation on 2 December 1804, Napoleon commissioned the court perfumer Francois Rancé to create a perfume for his wife. Rancé spent months working on a scent which he named ‘Joséphine’ and presented to Napoleon. The fragrance, that became enormously fashionable, combined the smell of two of Joséphine’s favourite flowers: rose and violet.

Unfortunately for Joséphine, as Napoleon became one of the most powerful men in Europe, he started to look for a wife more appropriate to his rank. As usual with royal marriages, the key issue was succession. After several years of marriage the couple had no children. In 1808 Joséphine learned of Napoleon’s decision to divorce her and marry the daughter of the Austrian Emperor Marie Louise.

Following her divorce, Joséphine preserved her title and income, and lived in her estate Château de Malmaison. There she gave herself to her love of flowers. She assembled an amazing botanical collection sourcing plants from all over the world. She had black swans, kangaroos, emus, zebras and other animals brought from Australia and Africa. They were allowed to roam free in the park. As a valuable contribution to art and science, her plants were documented in several publications by the Belgian artist and botanist Pierre-Joseph Redouté (1759–1840).

Joséphine also planted a large rose garden and stocked it with many rare and unusual varieties. Many of her roses were imported from Lee & Kennedy Vineyard Nursery in London, even though England and France were at war. Napoleon imposed an embargo on England, trying to cut it off from its European trade, but Joséphine’s shipments were allowed to pass unimpeded.

Joséphine also encouraged her gardeners to create new species of roses. Rose Souvenir de la Malmaison, was created in 1843 by Lyon rose breeder Jean Béluze and named in memory of Joséphine’s famous garden. This old favourite is still available and loved by gardeners today.

Four years passed after Joséphine’s divorce, when suddenly on 9 March 1814 a bunch of violets were brought to her by a 3-year old child of Napoleon and Marie Louise, Napoleon II, who was given by Napoleon the title King of Rome. The child was followed by Napoleon himself. Apparently, this was a happy occasion. Joséphine and Napoleon remained on good terms after their divorce, and some speculated that they continued to love each other.

But this was to be their last meeting. Two months later Joséphine died in Malmaison on 29 May 1814. Apparently at her funeral her coffin was covered with violates.

But following the death of Josephine the violet did not disappear from Napoleon’s life. It became an emblem for his followers and a symbol of fidelity to Napoleonic dynasty.

In 1813 Prussia, Austria and Russia formed a coalition against France. Napoleon was defeated at the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813. The coalition invaded France and captured Paris, forcing Napoleon to abdicate in April 1814. He was exiled to the small island of Elba, between Corsica and Italy. There Napoleon learned of Joséphine’s death from a French journal and stayed locked in his room for two days, refusing to see anyone.

On 20th of March, however, he secretly left Elba, arrived to Paris and declared himself Emperor. Previously he supposedly told his supporters that he would return when violets bloom in the spring. The supporters greeted him as Le Père de la Violette – the ‘Father of Violet’. They wore violets on their dress and decorated with them shops and the streets of Paris. Anything violet-coloured, whether ribbons or clothing, became a symbol of loyalty to the Emperor.

Napoleon himself, two days after his return from Elba, visited Malmaison in memory of some of happiest days of his life. Apparently he collected some violets from Josephine’s garden.

On this visit he was accompanied by Joséphine’s daughter Hortense de Beauharnais (1783–1837), later the Queen Holland. Napoleon is often blamed for treating Joséphine harshly, but a little known historical fact is that he was a very loving step-father to her two children. This is even though he was only twelve years older than his step-son Eugène.

The children remained loyal to him at his defeat, more so than even his own family. Hortense supported her stepfather during the Hundred Days and as a result was banished from France after his final defeat.

Napoleon’s return to power did not last long. The allies formed another coalition against France which defeated him at the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815. On 22 June Napoleon had to renounce the throne in favour of his young son. He was then exiled to the remote island of Saint Helena in the Atlantic, where he died in 1821 at the age of 51.

Napoleon’s last words on his death bed were: ‘France, l’armée, tête d’armée, Joséphine’ (‘France, the army, the head of the army, Joséphine’). In a medallion which he wore and with which he never parted were discovered two dried violets and a lock of hair.

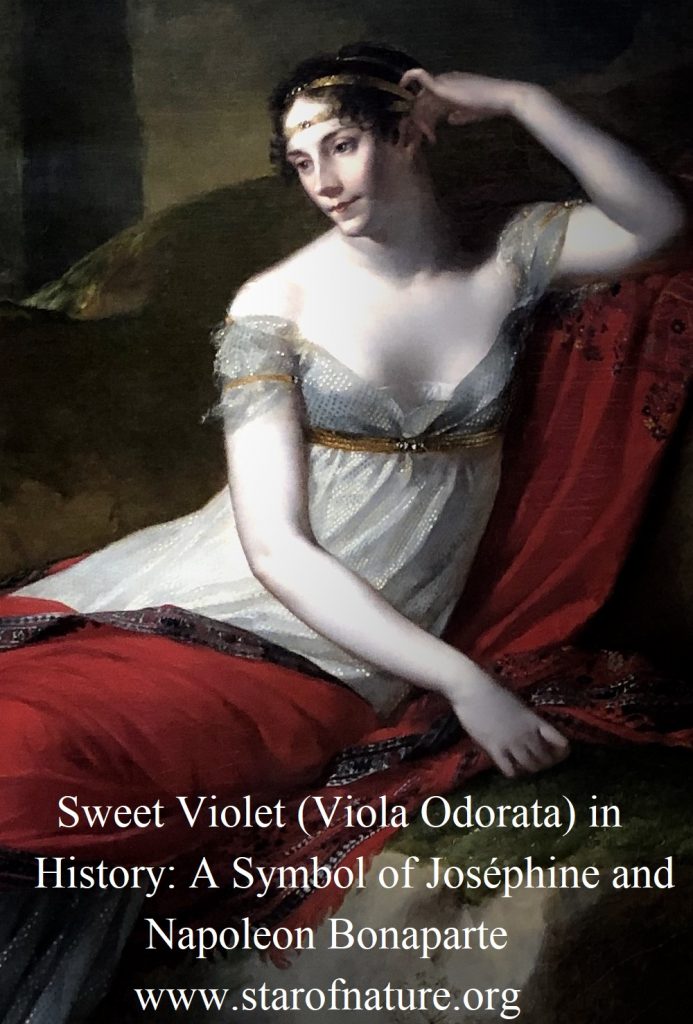

Featured image: Empress Joséphine by Andrea Appiani; pin: Pierre-Paul Prud’hon, the Empress Josephine, Musée du Louvre, Paris, by aiva.

Posts related to ‘Sweet Violet (Viola Odorata) in History: A Symbol of Joséphine and Napoleon Bonaparte’

Sweet Violet (Viola Odorata) and Parma Violet: How to Grow Forgotten Treasures

Growing Forget-me-nots; Forget-me-nots in Legends and History

Autumn crocus (Colchicum autumnale) – a Star of Early Autumn

The Golden Apples of Hesperides

A Mythological Garden in Odyssey

Roman Garden Style and Emperor Nero

Garden History: What did the Medieval Gardens Look Like?

Medieval Garden Plants and Layout: How to Design a Medieval Garden?

Pin ‘Sweet Violet (Viola Odorata) in History: A Symbol of Joséphine and Napoleon Bonaparte’ for later